His art was banned during the Third Reich. His pictures were confiscated. He was prohibited from painting. And yet Emil Nolde remained a fervent Nazi. By Stefan Koldehoff (Published on October 21, 2013 in Die Zeit)

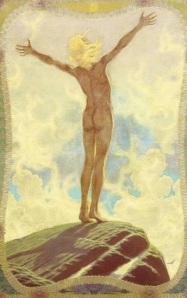

Schwü̈ler Abend (1930) © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

A half a century after his death Nolde is a superstar. Judged on the basis of the record highs his works fetch on the international art market, the attendance numbers at the exhibitions (once again over 100,000 recently in Baden-Baden) and the staggering print run of illustrated books, postcards, calendars and posters featuring his art, then Emil Nolde is by thoses standards one of the most prominent figures in the art world. Just as devotees of Claude Monet travel to Giverny, thousands of admirers make the pilgrimage to Seebüll in North Frisian to visit the Nolde House, where the painter resided from 1930 until his death. Six years ago a branch of the museum was built at the Gendarmenmarkt in the heart of Berlin.

Nolde’s luminous marshy landscapes and seas under brooding storm clouds, his biblical scenes and even the repetitive floral watercolors are a veritable hit with the public. His artwork is deemed avant-garde for its time while the vivid color and exuberance suggest timelessness. The artist himself is regarded as apolitical, although in a pinch expressionist artists are typically regarded as left-leaning. After all, many of them were persecuted by the Nazi regime. Nolde’s paintings too were banned as “degenerate”.

And yet the painter, a staunch anti-Semite, was whole heartedly committed to the Third Reich early on. In 1934 at the age of 67, he joined the National Socialist Working Group. Nolde began concealing this fact after the end of the war, rewriting crucial passages of his autobiography. In a talk commemorating Nolde’s 100th birthday back in 1967, the philologist and literary critic Walter Jens warned that one could not trust the rigor of the artist’s statements about himself.

He denounced his colleague Max Pechstein to Goebbels as a Jew

But then in the following year, the novel Deutschstunde became an overnight success. Written by the bestselling author Siegfried Lenz, the book depicts Nolde’s alter ego Max Ludwig Nansen as a resistor. Even later on, Nolde’s behavior has been down played again and again. Just this spring at a conference in Halle the consensus in the audience was that a painter of such beautiful work couldn’t have been a bad person. And this was the view even at the current show in Baden-Baden.

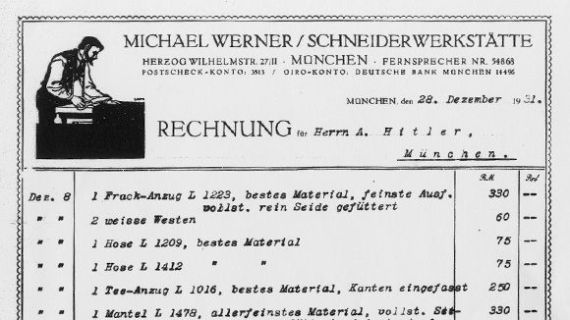

That he was such a person has now been proven again by a previously unknown document held privately in Switzerland. This newspaper article contains the first quotes to be published from the recently recovered six-page typescript. Handwritten notes were added to some of the paragraphs in the typed text, but the document lacks any salutation and merely bears the date, December 6, 1938. The author’s intention is abundantly clear however, with the first sentence casting aside any doubt:

For as long as I’ve worked as an artist I have publicly battled against the foreign infiltration of German art, against the dirty dealings on the art market and the disproportionately predominant Jewish influence everywhere in the arts. Now if that is the case, and I have been attacked and persecuted now for years by the side I championed and fought for, then there must be misunderstandings in need of clarification.

The sentences following this declaration consist of glowing endorsements of the Führer, Volk and Fatherland.

In his eyes the ur-German painter still felt misunderstood and unfairly treated almost six years after the Nazis assumed power and a few months after the regime had 1052 of his works removed from German museums, 48 of which were put on display for ridicule in the Degenerate Art exhibition. The authorities confiscated more of Nolde’s work than from any of his colleagues and yet he never left the slightest doubt regarding his loyalty to the regime.

Berlin art historian Aya Soika suspects the intended recipient of Nolde’s avowal was SS Group Leader Otto Dietrich, chief press officer of the Reich government. After the pogroms on Kristallnacht, Nolde may have complained to Dietrich about newspaper articles depicting the painter as “Jewish friendly”. “Shocking – even in the context it was created in”, Christian Ring said about the letter in speaking with Die Zeit. A few weeks ago, Ring became the director of the Nolde Foundation in Seebüll, which administers the painter’s estate.

The letter is part of a collection belonging to Nolde’s former drawing student Hans Fehr. Fehr was Swiss but held German nationalist beliefs and remained one of his closest confidantes until Nolde’s death. The Nolde Foundation just recently purchased the documents. “All the cards have to be on the table”, says Christian Ring. “There can’t be any more taboos.”

For decades the painter’s antisemitism and belief in Hitler were not mentioned in the literature, in part because the relevant sources were not accessible. It is only in recent years that scholars have been able to research and publish work on Nolde’s life during the Nazi period. Like the author Kirsten Jüngling, whose biography of the artist, Emil Nolde – Die Farben sind meine Noten (Emil Nolde, Colors Are My Music), was recently published by Propyläen.

But what we already know about the painter is enough to belie the image cultivated for the public—that of a mere victim of the Nazis. On April, 27 1933 just twelve weeks after Hitler’s accession to power, Nolde wrote an enthusiastic letter to the Norwegian art historian Henrik Grevenor in Oslo. In it he says the following: “So many things have happened through the political turbulence of this winter. And it occupies one continually because we are in the midst of experiencing the well-orchestrated and beautiful rise of the German people.”

A few days later he turned words into action. In their 2012 biography, Max Pechstein: The Rise and Fall of Expressionism, Bernhard Fulda and Aya Soika document how Nolde went to an official at the propaganda ministry in May of 1933 and denounced Pechstein as allegedly Jewish solely on the basis of his rival’s name. After Pechstein informed his accuser that this claim was untrue but could seriously endanger him and his family, Nolde nevertheless refused to officially rectify his statements.

In November 1933 Nolde wrote to Hans Fehr about attending a dinner to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch. An honored guest of Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, Nolde related the scene:

The commemoration was very moving. We saw and heard the Führer for the first time….The Führer is grand and noble in his efforts and is an affable man of action. Only a whole swarm of dark figures continues to idolize him in an artificially produced cultural fog. It appears that the sun will soon break though it and dissipate this fog.

1934 saw the publication of Jahre der Kämpfe 1902–1914 (The Struggles of 1902-1914), the second volume of Nolde’s memoirs. After reading the book, the art historian Ernst Gosebruch wrote to the Frankfurt collector Carl Hagemann in December 1934. “The numerous antisemitic and overly teutonic sections of the book reflect feelings we’ve come to expect from Nolde for years. I don’t find it very tasteful of him that he’s decided to express this at precisely this moment.”

Nolde had long hoped that the National Socialists would declare Expressionism as the official Nordic form of state art and place him, Nolde, on a pedestal. After all, unlike Kirchner and Pechstein, Erich Heckel, Hannah Höch, Otto Dix and George Grosz, he had never turned to social criticism but instead was a salt-of-the-earth German who remained true to Christian motifs. There was in fact movement in the direction he sought. A coterie around Joseph Goebbels consisting of Bernhard Rust, later the minister of culture, and Reich youth leader Baldur von Schirach attempted to influence the cultural policies of the regime to go in this direction. But he failed to persuade blood and soil ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, and made no headway with the “greatest artistic genius of all time”—Hitler himself ended the debate after the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, during which he had kept up liberal appearances. Goebbels responded by removing all of the Nolde paintings he had hung up in his private residence. 1937 witnessed the confiscation of the henceforth banned paintings from museums as well as the public ridiculing.

He fights for the “National Socialist cause with the fullest conviction”

The Degenerate Art exhibition was a heavy blow for Nolde. He turned directly to Goebbels on July 2, 1938 and requested the return of the confiscated paintings and the end of the defamations, “in particular because I have sided with the National Socialist movement from the very beginning and was virtually the only German artist to publicly fight against the foreign infiltration of German art, the dirty dealings of the art market and the intrigues during the time of Liebermann and Cassirer.”

Five months later, in the letter from December 6th that has recently emerged, Nolde confessed his unconditional commitment to the Nazi regime:

I revere the extraordinary and most recent form of government that National Socialism embodies; the work has been elevated to an honor. And I believe that our great German Führer Adolf Hitler lives and acts only on behalf of the justice and prosperity of the German people. And that he wants to know the complete truth regarding serious matters…and despite everything recently done to me, I have always and continually stood up for the National Socialist cause with the fullest conviction, at home and abroad. I have the impression that even today only a few people are aware of the culture war I led in 1910 against the prevailing foreign infiltration of all of the arts and against the all-powerful Jewish entity.

The 71-year-old also employed the most malignant form of Nazi-inspired antisemitic diction to provide further clarifications:

There are those who say my art work was sponsored and bought by Jews. This is false too. Some scattered paintings have found their way into the hands of Jews through the art market. Generally however they antagonize me. They have never wanted the purity and pristine German-ness in my art and have ridiculed it. All of my essential paintings are in the hands of Germans, have been purchased by Germans not in any way polluted by foreign influences, but who are conscious about their German-ness.

Emil Nolde continued to maintain his hope of being accepted by the regime early on in the war, submitting 54 pieces to the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts in the first two years of the conflict. On August 23, 1941, however, he received a notice from the chamber expelling him “on account of a lack of reliability” and forbidding him from working “in any professional…capacity in the area of fine art”. The chief of the Third Reich’s security services, Reinhard Heydrich, had sent a complaint previous to the ban, writing that “[T]he notorious art Bolshevik and leader of degenerate art, Emil Nolde, stated an income of 80,000 Reich marks in his tax declaration.”

The intentional warping of Nolde’s image began shortly after war ended. Until his death in April 1956 the painter himself did what he could to assist in the process. He censored sections of his four-volume autobiography that no longer appeared favorable, cleansing them of racist and antisemitic admissions and even partially distorting historical events.

In the second volume (The Struggles of 1902-1914), which includes the account of his conflict with Paul Cassirer and Max Liebermann in the Berlin Secession, he wrote:

Jews have a lot of intelligence and spirit, yet little soul and little creative talent….Jews are different than we are….the unfortunate presence of their settlements in the abodes of the Aryan peoples and their strong involvement in the innermost seats of power and culture have led to an unbearable situation for both sides.

This excerpt is missing from the current edition, as are some other sections dealing with the “danger of interracial mixing” and similar deadly and abstruse claims of Nazi ideology, without an indication that the omission was made. The latest edition of the four-volume memoir was published with the alterations in 2008 and includes the afterword from the one-volume abridged edition put out in 1976. In the latter, the former director of the Nolde Foundation, Martin Urban, wrote simply that “Nolde later revised the manuscript”.

“There’s nothing more to do except keep our mouths shut”

There were also glaring omissions in other publications that the foundation was responsible for in past decades or for which their staff had written articles. The artist could only be viewed as a victim of the regime. Whatever could not be reconciled or denied was excused as “political ignorance”. Only a few authors violated this status quo of silence and euphemism, such as Markus Heinzelmann who did not censor himself in 1999 in the Hanover catalogue on Nolde and his collector Sprengel.

Nolde’s biographer Kirsten Jüngling discovered proof that the historical record was deliberately distorted. In the State Archive in Hannover, she found a letter from May 29, 1963 written by the well-known art historian and early Nolde apologist, Werner Haftmann, and addressed to the painter’s collector Bernhard Sprengel.

Then the “Jewish Museum” in N. Y. exhibited 3 Noldes in their exhibition “Old Testament Paintings”. Meyers & Werner [an émigré journalist] called all the trustees and informed them about the “disgusting Nazi”. Of course that caused a commotion. I was also drawn in to some extent, because I was accused (it was whispered) that I had deliberately kept quiet about Nolde’s Nazi past. That’s true in fact, and I have no argument against it. [Nolde’s former secretary Joachim von] Lepel previously called upon me to remove any mention of it in my book. Finally I did so because after all something like this doesn’t have anything to do with the painter. The issue seems to have been clarified in the meantime. Thomas Messer, the director of the Guggenheim Museum, recently visited me. I promptly informed him at that point and he nipped it in the bud. Also of help there was Peter H. Janson, a professor at Columbia University as well as an old friend of mine who had informed me right at the beginning. There’s nothing more to do than keep our mouths shut. The exhibition apparently went well…”

The Kölner Dumont Verlag has been the Nolde Foundation’s publishing house for decades and is also the printer of Haftmann’s 1963 luxury volume on the “Unpainted Pictures” after 1941. This company has thus been earning money over this time period by publishing material containing a falsified historical record. Walter Jens resigned in protest from the foundation’s board of trustees in 1988, justifying his decision in part on the basis of the “scandalous editions” of Nolde’s writings.

Things have changed recently, however. While the unrevised autobiography continues to be sold, the painter’s dedication to Nazi ideology is no longer ignored in other publications issuing from the foundation and its staff. And the foundation in Seebüll has also ushered in a policy of transparency, having recently decided to allow scholars to thoroughly investigate Nolde’s connections with National Socialism.

Perhaps the result will be a new view of his art, of Emil Nolde’s stormy Nordic skies, his marshy landscapes and flower beds. It certainly won’t hurt postcard sales.